A review of Dimopoulus, Konstantinos: Virtual Cities; Unbound, London, 2020. ISBN 978-1-78352-848-6.

The Pelennor Fields around Minas Tirith, as rendered in Peter Jackson's film of The Return of the King, are at best rough grazing; the land outside Cintra, in Netflix' The Witcher series, is little more than moorland. This cannot be right.

Cities require large supplies of food, and consequently all pre-modern cities are built in areas of very high agricultural productivity. To support a city the size of Minas Tirith, the Pelennor must needs be not as productive as the Shire – because the Shire supports only its own peasantry – but substantially more productive. Of course, what this means in the modern period is that, as the cities expand, that very high quality agricultural land is built over and lost, but that is not what this essay is about.

But a city requires more than a significant supply of food. A successful city also requires a strategic reason to be where it is.

In the world I've been writing about for The Great Game, I have one city which completely breaks the rule of having an adequate agricultural hinterland, but there's a strategic reason for this. The city of Hans'hua controls the only possible water supply where the main trade route from the north coast of the continent to the south crosses a high desert plateau. Water is so valuable here that the city can, by taxing the supply of water to merchant caravans, afford to import substntially all its food.

At the time period of the game, this city has been, although small, very rich (and consequently, has excellent defences); its wealth is threatened, however, because advances in ship technology have opened up a new sea route, bypassing Hans'hua, and its decline has begun.

Another city, Tchahua, has grown from a fishing village to a modestly prosperous silk-weaving centre; but its fortunes, too, have suddenly changed. It controls one of the few deep water ports on the south coast suitable to the new ships, making it suddenly a vitally important node in the trading network; but because it has no history of being wealthy, it doesn't yet have defences commensurate with its new strategic importance, and is therefore a military target for every other power.

So cities – real cities – are not just consumers of resources (and thus, necessarily, producers of goods or services which they can trade for those resources); they're not just places of strategic importance. They're also dynamic entities, changing in response to the pressures that the wider economic and geopolitical forces impose upon them.

A virtual city doesn't, intrinsically, need to conform to these rules; but to be persuasive, to play a significant part in a persuasive narrative, it ought to do so, I think.

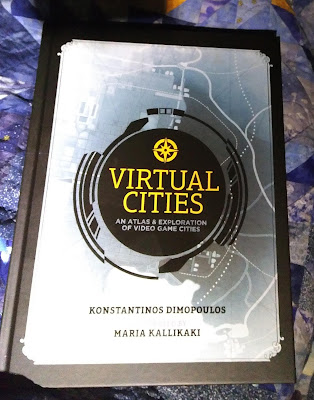

This is the pool of meditations into which Konstantinos Dimopoulos beautifully illustrated new book, Virtual Cities, has dropped.

The book is a substantial volume, as large and weighty as the telephone directory for any of the cities it describes. It is beautifully produced, colour printed throughout, elegantly and consistently designed, easy to navigate.

|

| Entry for Novigrad |

I'll say here that the style of illustration surprised and initially disappointed me. I had expected that the illustrations would be, at least nearly, screenshots taken from the particular games. They are not; instead, they are all drawn, in pen and ink, by a single artist, Maria Kallikaki. On reflection this is a good choice. It preserves the conceit from the 'tourist guide' that these are places one might really visit, and, at the same time, gives a cohesive visual style to the whole work.

I do not think that, for many people, this will be a book to read from cover to cover; certainly I have not done so. Rather, I have sought first the entries for some familiar – to me – virtual cities, like Novigrad, Whiterun and Dunwall, and then browsed to the entries for cities I have on my virtual bucket list but have not yet visited, and from there on to still others like Neketaka and Gabriel Knight's New Orleans, which I hadn't previously been aware of but now want to visit.

Of course this isn't – couldn't be – a comprehensive guide to all virtual cities, but rather a curated sample. I'm a little disappointed to find none of Rockstar Games' cities, as some of these, especially in recent games, are, I believe, very well executed. Most of the other major developers of games which present realistic urban worlds are represented.

BioWare are represented only by the Mass Effect series' Citadel, which I think is fair; none of BioWare's cities, that I've visited, has seemed to me well thought out or credible, they struggle even with villages – which, for a company with such resource and talent and which does so much else reasonably well, is surprising. Valve has City 17. Blizzard has Tarsonis. Infocom, Rockvil. Obsidian has New Vegas and Neketaka. Ubisoft are represented by Assassin's Creed: Syndicate's realisation of London, an entry which has made me more than ever eager to experience this for myself.

|

| Map of Novigrad |

CD Project Red are represented only by Novigrad. It's a reasonable choice; arguably their best realised city at the time the book was being written. Visima, in the original The Witcher game, was astonishingly well realised for its date; Beauclair is the most beautiful city they have released yet; Night City, due to open to visitors a month from now, promises to be by far their most ambitious and complex. Yet, excluding Night City, none of Visima, Beauclair or indeed Oxenfurt has any significant feature which Novigrad does not, and of them all, Novigrad is the largest and most complex.

Dimopoulos describes it as "one of the biggest, most thoroughly fleshed out, fantasy towns in gaming". I'd quibble a little with "fantasy," since Novigrad, although certainly fictitious, is so thoroughly grounded in Eastern Baltic history; but otherwise I wouldn't dissent from that judgement.

Of course, besides these big development houses, many smaller developers are represented, too.

Of course, not all these games consider the economic relationships of their cities to their hinterlands, although the better ones do. Of course, in not all of these games are geopolitical events even modelled, in still fewer do they cause observable change within the cities. And yet there is learning to be had from all these cities. Even those which fail, teach; because we can learn how they fail, and avoid it.

Modelling an entire city and its economy, making it traversible and navigable, and filling it with interesting, believable characters and action, is a complex, interesting task. There are a lot of moving parts. It takes thought.

And good books, which provoke thought, which introduce me to new cities to study, help enormously. For any geek interested in what makes game worlds tick, this book is a must have.

No comments:

Post a Comment