|

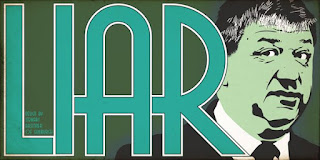

| Alistair Carmichael, who proved that politicians can lie with impunity. Picture by Stewart Bremner |

Time moves on; there are other problems in the news publishing environment which existed then but which are much more starkly apparent to me now; and there are some issues which are authentically new.

Why News Matters

Challenges to the way news media works are essentially challenges to democracy. Without a well-informed public, who understand the issues they are voting on and the potential consequences of their decisions, who have a clear view of the honesty, integrity and competence of their politicians, meaningful democracy becomes impossible.We need to create a media which is fit for - and defends - democracy; this series of essays is an attempt to propose how we can do that.

So what's changed in the past twelve years? Let's start with those changes which have been incremental.

History Repeats Itself

Proprietors have always used media to promote their political interests, and, for at least a century, ownership of media has been concentrated in the hands of a very few, very rich white men whose interests are radically different from those of ordinary folk. That's not new. But over the past few years the power this gives has been used more blatantly and more shamelessly. Furthermore, there was once an assumption that things the media published would be more or less truthful, and that (if they weren't) that was a matter of shame. No longer. Fake News is all too real.Politicians have always lied, back to the beginnings of democracy. But over the past decade we've seen a series of major elections and referenda swung by deliberate mendacity, and, as the Liar Carmichael scandal shows, politicians now lie with complete impunity. Not only are they not shamed into resigning, not only are they not sacked, successful blatant liars like Liar Carmichael, Boris Johnson, David Davis, Liam Fox and, most starkly of all, Donald Trump, are quite often promoted.

Governments have for many years tried to influence opinion in countries abroad, to use influence over public opinion as at least a diplomatic tool, at most a mechanism for regime change. That has been the purpose of the BBC World Service since its inception. But I think we arrogantly thought that as sophisticated democracies we were immune to such manipulation. The greater assertiveness and effectiveness of Russian-owned media over the past few years has clearly shown we're not.

The Shock of the New: Social Media

Other changes have been revolutionary. Most significant has been the rise of social media, and the data mining it enables. Facebook was a year old when I wrote my essay; Twitter didn't yet exist. There had been precursors - I myself had used Usenet since 1986, others had used AOL and bulletin boards. But these all had moderately difficult user interfaces, and predated the mass adoption of the Internet. It was the World Wide Web (1991) that made the Internet accessible to non-technical people, but adoption still took time.Six Degrees, in 1997, was the first recognisably modern social media platform, which tracked users relationships with one another. Social Media has a very strong 'Network Effect' - if your friends are all on a particular social media platform, there's a strong incentive for you to be on the same platform. If you use a different social media platform, you can't communicate with them. Thus social media is in effect a natural monopoly, and this makes the successful social media companies - which means, essentially, Facebook, Facebook and Facebook - immensely powerful.

What makes social media a game changer is that it allows - indeed facilitates - data mining. The opinions and social and psychological profiles of users are the product that the social media companies actually sell to fund their operations.

We've all sort of accepted that Google and Facebook use what they learn from their monitoring of our use of their services to sell us commercial advertising, as an acceptable cost of having free use of their services. It is, in effect, no more than an extension of, and in many ways less intrusive than, the 'commercial breaks' in commercial television broadcasts. We accept that as kind-of OK.

It becomes much more challenging, however, when they market that data to people who will use sophisticated analysis to precisely target (often mendacious) political messages at very precisely defined audiences. There are many worrying aspects to this, but one worrying aspect is that these messages are not public: we cannot challenge the truth of messages targeted at audiences we're not part of, because we don't see the messages. This is quite different from a billboard which is visible to everyone passing, or a television party-political broadcast which is visible to all television watchers.

There's also the related question of how Facebook and Twitter select the items they prioritise in the stream of messages they show us. Journalists say "it's an algorithm", as if that explained everything. Of course it's an algorithm; everything computers do is an algorithm. The question is, what is the algorithm, who controls it, and how we can audit it (we can't) and change it (see above).

The same issue, of course, applies to Google. Google's search engine outcompeted all others (see below) because its ranking algorithm was better - specifically, was much harder to game. The algorithm which was used in Google's early days is now well known, and we believe that the current algorithm is an iterative development on that. But the exact algorithm is secret, and there is a reasonable argument that it has to be secret because if it were not we'd be back to the bad old days of gaming search engines.

Search, in an Internet world, is a vital public service; for the sake of democracy it needs to be reasonably 'objective' and 'fair'. There's a current conspiracy theory that Google is systematically down rating left-wing sites. I don't know whether this is true, but if it is true it is serious; and, whatever the arguments about secrecy, for the sake of democracy we need Google's algorithm, too, to be auditable, so that it can be shown to be fair.

Tony Benn's five famous questions apply just as much to algorithms as to officials:

- What power have you got?

- Where do you get it from?

- In whose interests do you exercise it?

- To whom are you accountable?

- How do we get rid of you?

Facebook and Google need to answer these questions on behalf of their algorithms, of course; but in designing a system to provide the future of news, so do we.

To Everything, There is a Season

There's a lot to worry about in this situation, but there is some brightness to windward: we live in an era of rapid change, and we can, in aggregate, influence that change.Changing how the news media works may not be all that hard, because the old media is caught in a tight financial trap between the rising costs of printing and distribution and the falling revenues from print advertising. Serious thinkers in the conventional media acknowledge that change is necessary and are searching for ways to make it happen.

Creating new technology and a new business model for the news media is the principal objective of this series of essays; but it isn't the only thing that needs to be done, if we are to create an environment in which Democracy can continue to thrive.

Changing how social media works is harder, because of the network effect. To topple Facebook would require a concerted effort by very many people in very many countries across the globe. That's hard. But looking at the history of search engines shows us it isn't impossible.

I was responsible for one of the first 'search engines' back in 1994; Scotland.org was intended to be a directory to all Scottish websites. It was funded the SDA and was manually curated. Yahoo appeared - also as a manually curated service - at about the same time. But AltaVista, at the same time, launched a search engine which was based on an automated spidering of the whole Web (it wasn't the first engine to do this), which, because of its speed and its uncluttered interface, very rapidly became dominant.

Where is AltaVista now? Gone. Google came along with a search engine which was much harder to 'game', and which consequently produced higher-quality search results, and AltaVista died.

Facebook is now a hugely overmighty subject, with enormous political power; but Facebook will die. It will die surprisingly suddenly. It will die when a large enough mass of people find a large enough motivation to switch. How that may be done will be the subject of another essay.

No comments:

Post a Comment